In a study published in the journal Science Advances, Dr. Nixon Abraham’s group from the Biology Department of IISER Pune showed in a mouse model that the nose can sense wind speed in addition to smells, and that chemical and mechanical inputs together constitute the olfactory (sense of smell) perception.

The researchers believe that this is an important revelation on the current understanding of the sense of smell that opens new avenues for exploring the intricacies of sensory processing in the brain. “Our findings show that the olfactory system in the brain doesn’t just process chemical information from odours, but also integrates mechanical information from air movements inside the nasal cavity,” said Dr. Nixon Abraham, who led the study. “In essence, the nose acts as a dual sensor - one that can both smell and feel the air,” he said.

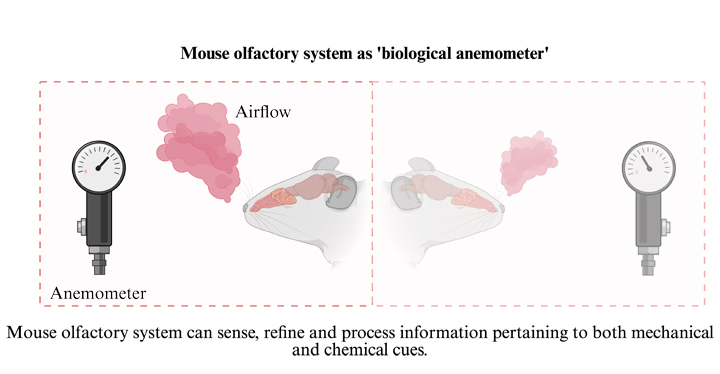

Giving further context to the research question addressed in this paper, Dr. Abraham said, “An anemometer measures the wind speed. In neuroscience, our understanding has traditionally emphasised the brain’s role in processing sensory information gathered through various sensors such as the eyes, nose, ears, skin, and proprioceptive receptors. While the brain integrates inputs from these sensory systems to form a cohesive perception of the environment, it has not been presumed to possess a specialised mechanism analogous to an anemometer for directly detecting and discriminating wind speed. Our findings present a fascinating possibility: the existence of a unique brain mechanism dedicated to sensing the wind speed, that of a biological anemometer.”

Smelling the air, literally

PhD student, Sarang Mahajan, who is the first author in this study, explained the experimental details. In a series of behavioural experiments, mice were trained to distinguish between different airflows, wherein they could identify different airflows with accuracy close to 90%. When the team recorded brain activity using advanced techniques such as in vivo calcium imaging, genetic manipulations, and optogenetics, they found that specific inhibitory neurons in the olfactory bulb, the brain’s first relay station for smell, were critical for processing airflow information.

When the activity of these inhibitory circuits was artificially increased or decreased, ability of the mice to learn airflow-based tasks changed significantly. Strengthening the inhibitory signals slowed learning, while reducing inhibition made the animals learn faster. Interestingly, the same manipulations produced the opposite effects in odour-learning tasks.

“This revealed that the brain uses different levels of inhibition to refine airflow and odour information. The olfactory bulb is essentially balancing two sensory streams, chemical and mechanical, to create a more complete perception of the world,” explained Dr. Mahajan.

Air helps enhance smell

The researchers also found that when very faint odours were paired with air movements, the mice learned to recognise the odours much more quickly. This suggests that airflow cues enhance the brain’s ability to detect weak smells, allowing animals to better navigate their surroundings where odours are carried by varying airflows.

“This work provides the first experimental proof that the olfactory circuits can act as ‘anemo-detectors’, sensing air through the nose,” said Dr. Abraham. “It opens a new way of thinking about smell as a multimodal experience, one that combines both chemical and physical information.”

A new perspective on olfaction and beyond

The researchers shared that this discovery has broad implications for neuroscience, robotics, and medicine. Understanding how the brain integrates airflow and odour information could inform the design of bio-inspired sensors that detect chemicals more efficiently in varying environmental conditions. It could also help explain why changes in breathing patterns affect smell perception in humans, especially during respiratory illnesses or disorders that alter airflow through the nasal passages.

“Beyond its scientific significance, this study highlights the value of interdisciplinary research that connects behaviour, physiology, genetics, and neuro-engineering to uncover fundamental mechanisms of perception,” said Dr. Abraham, pointing to the significance of applying multiple types of expertise in understanding the complexities of how the sense of smell works.

Funding and Support

This research received funding from the DBT-Wellcome India Alliance and the Department of Science and Technology (DST), Government of India. Additional support came from the Department of Biotechnology (Govt. of India), core IISER Pune research grants, and student fellowships. The authors acknowledge the contributions of their laboratory colleagues and technical staff at the National Facility for Gene Function in Health and Disease (NFGFHD), IISER Pune.

Citation

Sarang Mahajan, Susobhan Das, Suhel Tamboli, Sanyukta Pandey, Anindya S. Bhattacharjee, Meenakshi Pardasani, Priyadharshini Srikanth, Shruti D. Marathe, Avi Adlakha, Lavanya Ranjan, and Nixon M. Abraham (2025). Mouse olfactory system acts as anemo-detector and anemo-discriminator. Science Advances DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adq8390